The role of popular media in how a community is perceived, either outside or from within that community, cannot be denied. This becomes stronger when the community that is being represented is a marginalized one and the medium through which is its being represented is as powerful as Bollywood. Bollywood is the heart of Hindi cinema in India and the Indian film industry is the leading film industry in the world, at least when it comes to the number of films produced per year. Bollywood movies have not only propelled people into almost God like figures, but these movies have also become an important part of the culture, be it the songs that one dances to on weddings or in pubs, or the way certain movies have been running in theatres for years on end. Not only this, Bollywood movies have also raised several important issues and at the same time have reflected the realities of the everydayness of lived lives. From movies being set in extremely traditional family settings such as ‘Hum Saath Saath Hain’, to movies that have touched newer topics, such as the more recent ‘Tumhari Sullu’ starring Vidya Balan, movies also reflect what the audience is willing to consume as entertainment how perception about various things such as family, women and work have changed. Yet there is a visible gap in mainstream representation of people from the LGBTQ+ community.

Though, much work has been done on how even the miniscule representation of the LGBTQ+ community in Bollywood is mostly negative, either in the forms of being depicted as either villains or comic reliefs, this article doesn’t attempt to that. Here, I am looking at three articles viz, The queer rhetoric of Bollywood – A case of mistaken identity by Rohit. K. Dasgupta, Queering Bollywood: Alternative sexualities in popular Indian cinema by Gayatri Gopinath and then attempting to tie these articles up by engaging arguments from Compulsory gender and transgender existence – Adrienne rich’s queer possibility by C.L. Cole &Shannaon L.C. Cate. The former two articles make a case for viewing Bollywood movies differently to actually realize its queer potential.

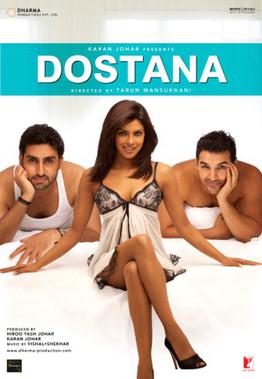

In his article, Dasgupta (2012) says that there needs to be a new way to understand how queerness plays out in Bollywood. He emphatically makes a case for why this needs to be Queer rhetoric and not a ‘gay’ or a ‘trans’ rhetoric because of the fluidity that ‘queerness’ provides, it’s allegiance to socio-political transformation and how it has escaped academic pinning down of sorts. He mentions that there are various strands on which a Queer movie can be identified viz whether ‘alternate’ sexual identity or sexual desire is expressed, whether the queer viewing audience’s pleasure is focused upon, that is, keeping the viewer in mind. Since popular Hindi cinema doesn’t do any of this, he proposes a third strand where one needs to look at the slippages between the real identity and the mistaken identity and then how these mistaken identities help in building up an alternate queer narrative in a world of family and traditions. Though, at the end, heterosexuality is inevitable but this strand plays with the ambiguity of sexual desires. In making a case for the mistaken identity, he puts forth the example of two films; ‘Dostana’ and ‘Kal ho na ho’. In both these movies, there is a homosocial triangle between the two male leads with the female lead mostly acting as a conduit. While Dostana is premised on the two male characters posing as gay for an apartment, in ‘kal ho na ho’, the character of Kantaben catches the two leads in situations that are homoerotic, if not homosexual. He says that most of the humor in Dostana if not in Kal Ho Na Ho is not homophobic but is derived from the mistaken identity of the two characters. Though some images are stereotypical, but other stereotypes related to family and others are subverted or aren’t depicted. The ending of both the movies can also be seen as Queer as Dostana ends with neither of them ending up with the female lead and‘Kal ho na ho’ ends with a marked gap that one of the male character’s death leaves in the life of other characters. He argues that it’s moment like these that create a foucauldian heterotopia in popular movies. The point isn’t the politics of good or bad representation in these movies, but how we read them.

Dasgupta’s second strand of the location of the viewer is something that he derives from Gayatri Gopinath’s paper. For both of them, the viewer is the text. While centering the location of viewer, Gopinath (2000) says that although the mainstream Hindi movies aren’t producing content that will directly please the queer audience, or something that queer viewer will relate to, that is because these movies are being shown to a viewer within a nationalist framework located the country. When the viewer is located in a South Asian diasporic context, the reading of these images change. She especially focuses of song and dance sequence so common to Bollywood and says that

‘Cinematic images which in their “originary” locations simply reiterate conventional nationalist & gender ideologies may, in a South Asian diasporic context, be refashioned to become the very foundation of a queer transnational culture. Queer reading allows us to read queer desire in otherwise heteronormative/heterosexual depictions.’ (284, Gopinath, 2000)

She divides her paper into four parts where she talks about female homosociality, male bonding, cross dressing and trans* expressions and the clear depiction of hijra and gay individuals. She cites many examples in the first two cases, whether the friendship of the two individuals is not only on a homosocial scale, but can also be located on a homoerotic scale. In the latter half, she shows that how effeminate characters are allowed to exist in movies longer than the masculine female and how sometimes clear boundaries are drawn between the gay and hijra characters

I would now like to submit that all the people that are being talked about till now, be it the viewers, the characters, the actors playing these parts, the writers, everyone exists on a transgender continuum as explained by C.L. Cole and Shannon L.C. Cate in their paper. They are expanding on the concept of the lesbian continuum that Adrienne Rich (1980) put forward, which said that all women exist on the lesbian continuum regardless of them identifying as a lesbian or not. The way women bond with each other is markedly different from the way men do it and this is what posits their location on the continuum. Similarly, Cole and Cate are saying that in our day to day existence we do many things that would actually transgress the boundaries of acceptable gender expressions and behavior, even if one doesn’t identify as trans. This is truer for Bollywood, where commercialization is the driving force and commodification of bodies, be it for the male or female gaze has risen to extreme extents. By placing all these individuals and cultural imageries on the transgender continuum, the actual potential of a gender-free society can be realized.

References

Gayatri Gopinath (2000) Queering Bollywood, Journal of Homosexuality, 39:3-4, 283-297,

Cate, C. L., & C Cate, S. L. (2008) Compulsory gender and transgender existence: Adrienne rich’s queer possibility. Women’s studies quarterly, 36(3/4), 279-287.

Dasgupta, R. K. (2012) The queer rhetoric of Bollywood: A case for mistaken identity. Interalia. Retrieved from http://www.interalia.org.pl/index_pdf.php?lang=en&klucz=&produkt=1353788763-695